Photography is the art and craft of capturing light, whether via silver halide chemistry on film, or via silicon on a sensor array. “Capturing light” is probably the key part of this definition: unlike the popular perception that we photograph people or things, it is impossible to actually render anything in the absence of light. All we can capture is light emitted or reflected (mostly reflected) by our photographic subject matter.

Why do we care about a photo? Generally because it stirs our emotions. Emotions can be stirred for many reasons, and due to many associations (Marcel Proust’s account of emotional reminiscence stirred by an odor comes to mind). An emotionally resonant image that is technically imperfect will trump a technically perfect but banal image any time.

Leaving aside imagery where the pure storytelling packs a wallop, powerful photos use light emotionally. Even graphic human interest photos are more powerful when they use light to their advantage. To summarize, we capture light not things. Emotional resonance is what matters in imagery. Therefore, powerful images manage to use light to convey an emotional response in the viewer. What should your take-away from this syllogism be? I think there are three simple conclusions that all good photographers recognize as guiding principles, and strive to master:

- If you want to be a better photographer, train yourself to see light and not objects.

- Light inspires, directs and misdirects when it is captured as the incredible force it is. Use all of this in your work: the force, the power, the inspiration, the direction and the misdirection.

- Uniform and moderate light is rarely as interesting as strong lighting. Think of it this way: without evil for comparison, how do we know what “good” is? Light is the same way. You often can’t really see it unless there is also darkness.

In my high-key image of Irises in a Vase (shown far above) I purposely created a highly artificial construct of light that seems almost blinding—and therefore obscures details. This image does not look the way it would be rendered in a single accurate capture, but is more emotionally compelling because the apparently overwhelming light has left only the painterly details, with enough visual clues for the viewer to interpolate the rest. With Boathouse Still Life (above) the emotional appeal is achieved because of the partial illumination. In a generally low-key image, the composition with nautical rope behind it is lit by an apparently momentary shaft of light.

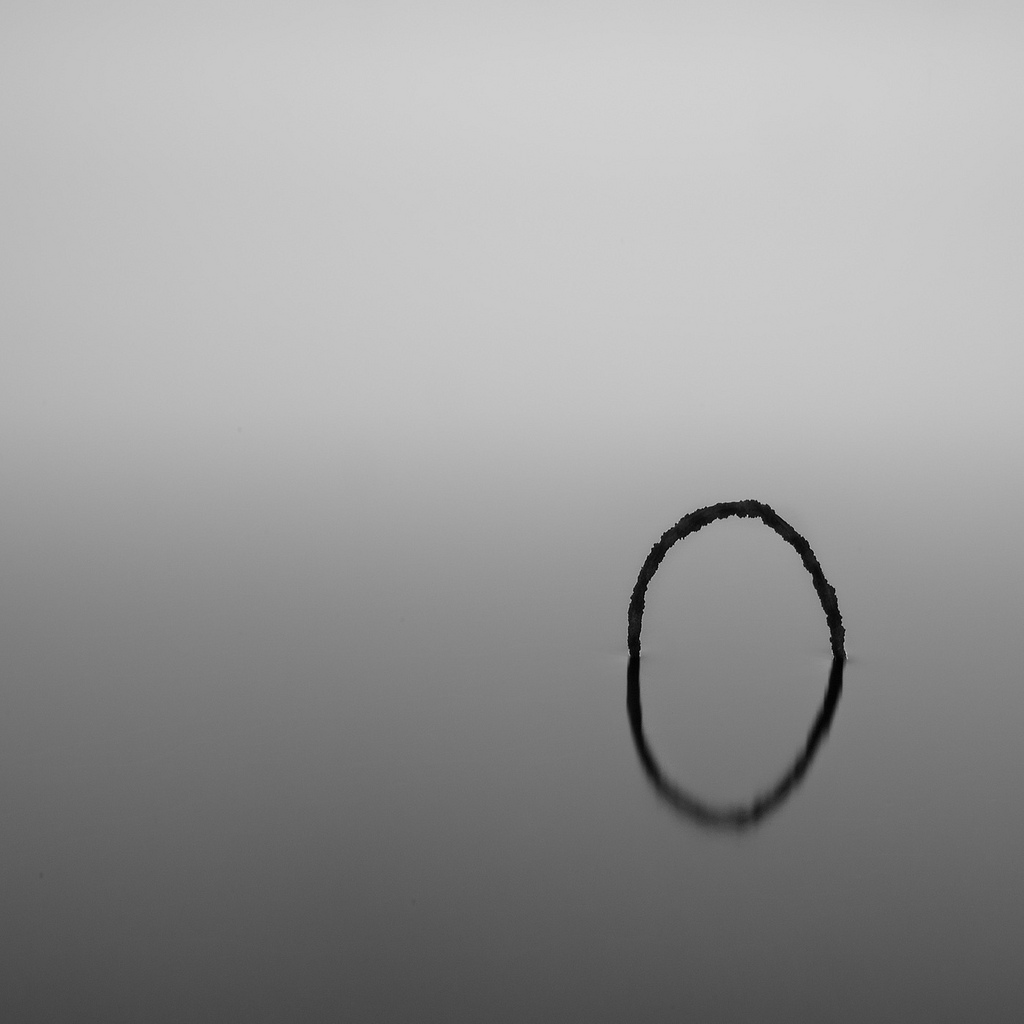

In Story of O (above) the action is in the gradation of light, from the light gray in the distance to the darker gray in the foreground, and the contrast with the black outlined shape. A sense of mystery always adds to the emotional appeal of an image, and the relationship of the background gradient to the “circle” foreground is indeed mysterious, bringing several different kinds of light into play. I like to quote the American poet Randall Jarrell, who once said that “Art being bartender is never drunk.” I take this to mean that my viewers don’t have to know what is going on in an image, and maybe even shouldn’t—but as “bartender” I must. This means first and foremost learning to use and control the emotional impact of light in my imagery. Related stories: More about Story of O; more about Boathouse Still Life. Also check out Becoming a More Creative Photographer (a set of articles with exercises on Photo.net).

Pingback: Belying Apparent Simplicity

Bill Coughlin

26 Jan 2016Thank you!