I was recently asked by an art gallerist I work with to help educate some clients regarding my printmaking. Essentially the issues come down to exploring how my prints differ from mass-produced inkjet prints, since largely the same equipment is used. In contrast to those you get from Costco or giclees from an art reproduction company, my prints require a great deal of hand labor. My FAQ: Prints by Harold Davis covers much of this ground, and I also think the following discussion helps put things in perspective.

What printer do you use?

We own a number of inkjet printers, and have worked extensively with both Canon and Epson printers. But I am happiest so far with my Epson Stylus Pro 9900. This is a behemoth of a printer that occupies the room in our house formerly known as the dining room! It is shown below a while back when it was first delivered.

Prints from a high-end inkjet printer such as the Epson 9900 go by a variety of names, including:

- Inkjet print —I think you’d rather suspect this term would be in use;

- Pigment print —the printer lays down pigment rather than altering an emulsion as in traditional photographic printing;

- Giclee —named after the French verb gicier, “to spurt,” a neologism specifically coined to avoid the “stigma” of being called an inkjet print; and

- Piezo print —named after the kind of print head that is in the printer.

Personally, I don’t think there is much in the name, and all these terms mean the same thing. After all, a rose by any other name is still a rose, and all that. Overall, I tend to favor “pigment print”.

The widespread confusion of terminology relates to the incredible spectrum of uses for this technology: You can buy inkjet prints at Costco, where they are honestly labeled, you can buy the somewhat pretentiously named giclee prints from companies that reproduce art, and you can collect one-off artisanal pigment prints from solo artists such as Harold Davis who make these prints one at a time in their studio.

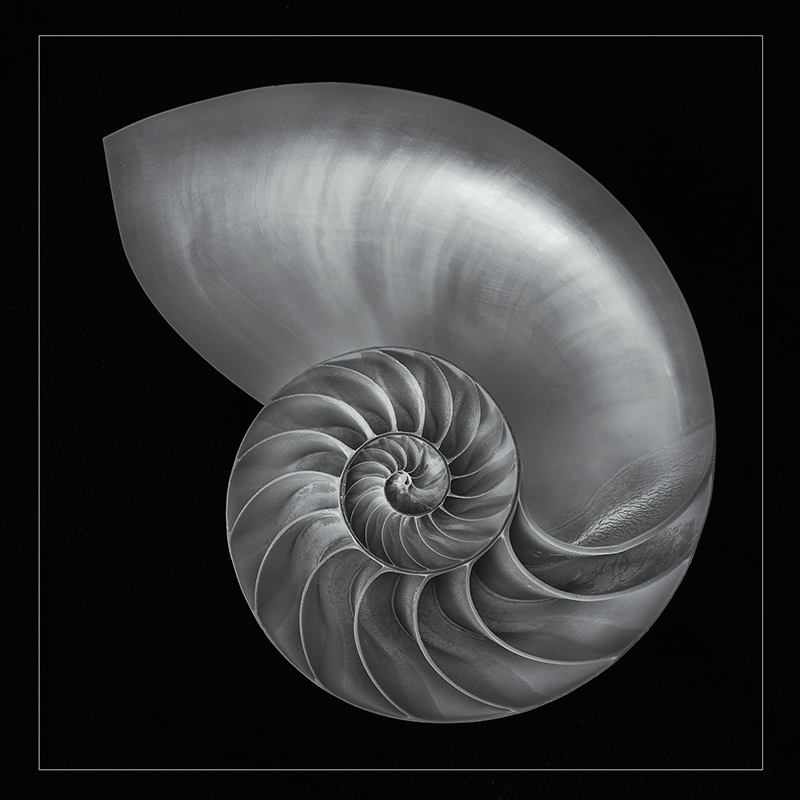

The difference between these various uses isn’t really the gear that is involved, just as the difference between mediocre and great photography is rarely the gear the photographer uses. Quality in digital printmaking really comes down to knowing the quirks of the printer, understanding how to get the most out of digital workflow, how the technology is used, the vision behind the printmaking, and the care and time that is spent on each individual image.

I would emphasize the point that in my opinion just as much craft, skill, and artistry goes into making a good artisanal digital inkjet print as ever went into a print made in the chemical darkroom. The vision and care required are much the same, but the specific skills required are different.

What papers do you use?

I love paper in all its types and manifestations, and am constantly playing with and experimenting with paper from various sources. That said, I am mighty partial to papers by Moab from Legion Paper. (Full disclosure, I am a Moab Master and have a very cordial relationship with the great folks at Moab.) One thing Moab has going for its papers is that they do a great job of creating ICC printing profiles for specific printers, which helps me make the output files for the prints I want with a minimum of fuss.

I do try to match the paper I use to the image. It’s interesting, because sometimes an image will look good printed on multiple substrates, albeit with very different looks—and other times there is really only one good possibility.

How long does it take you to make a print?

This depends on many variables, and absent a specific image file and paper it is a little hard to say. Larger prints are usually (but not always) much harder to print than smaller prints. Prints with a great deal of black can be hard to print (because they show flaws easily), as can prints with a white background (because dust and other problems show up).

Some papers are simply tougher to handle than others. Examples of paper that have some delicate handling characteristics include Moab Slickrock Silver and Awagami Unryu. These substrates are unique and beautiful, but sometimes beauty has its payback—in this case, these papers require extra attention as they go through and come out of the printing process.

If you include output file preparation, printing, and post-printing issues, an average print might take something like five to ten hours, in some cases a bit less, and in some cases much more: Sometimes I have to print an image 20 times until it is right and I get that one good print.

The take-away should be that considerable effort and time goes into every print that I make. There is no such thing as “mass printing” in my studio. Of course, this leaves out the hours or weeks it may take me to make my images in the first place.

Are your prints in limited editions?

The concept of a limited edition comes from traditional non-photographic printmaking. In a tradition that evolved from the nineteenth century, first one made an etching plate, or lithographic stone, then ran off prints using the plate or stone. When the edition was complete with 100 prints or so, the plate or stone was canceled or destroyed so that no more prints could be made. The point of this kind of limited edition was that a given plate or stone could only support a certain number of copies on press before it started to deteriorate and wear out, and also of course to indicate the scarcity of the print.

To me, this kind of limited edition makes relatively little sense with photography. You could even say, “limited” sense, or no sense at all.

Unless one is willing to destroy the original image file (which I, and most photographers, are certainly

not willing to do), it almost smacks of deception. Here’s why: It has been common with a really popular images for the photographer to switch a detail slightly, for example make the image slightly larger or smaller, and then keep making prints when the original-sized edition runs out of print numbers. This makes no real sense to me and doesn’t seem right.

What I affirmatively do is keep track of my prints. That way, I can look up how many copies have been printed of any image. Knowledgeable gallerists and collectors I have discussed this with tell me that this provides them with all they really need—a good sense of how many of a given print have been made. From there they can derive information about how popular and/or scarce a given print is.

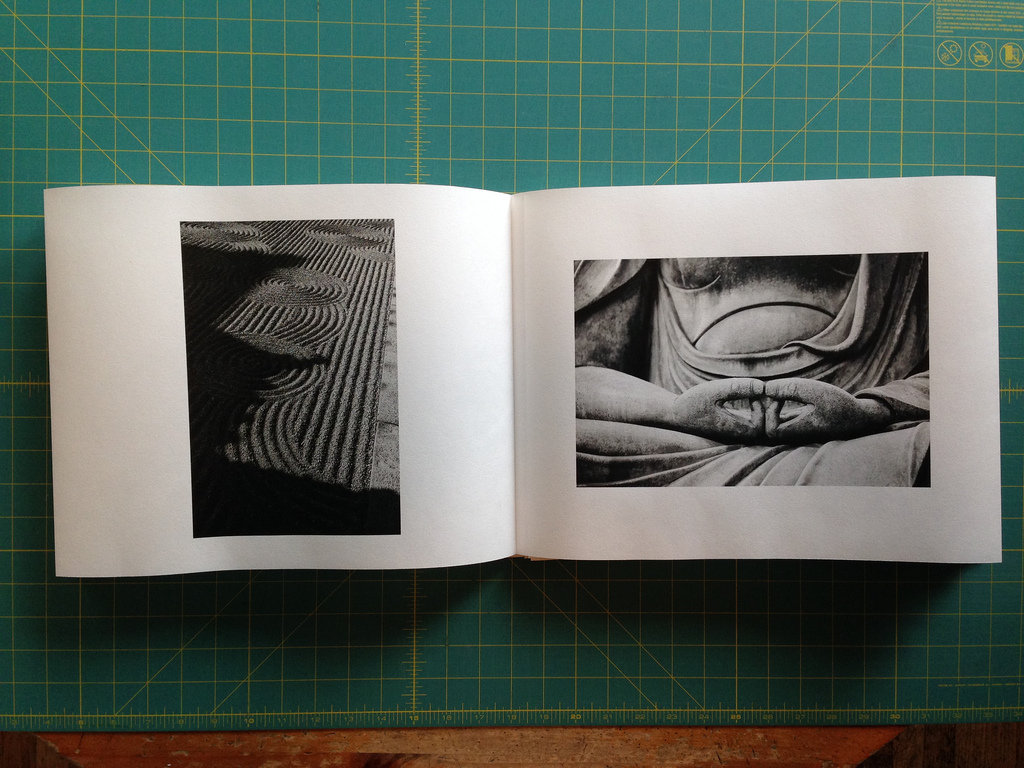

Note that on the other hand I do produce portfolios in limited editions. In the case of a limited edition portfolio, the fact that it is limited shows how much hand effort goes into each one made. Examples of limited edition portfolios include my Botanique, Monochromatic Visions, and Kumano kodo portfolios. It’s important to be clear with these portfolios that it is the portfolio—and not the prints—that is part of a limited edition.

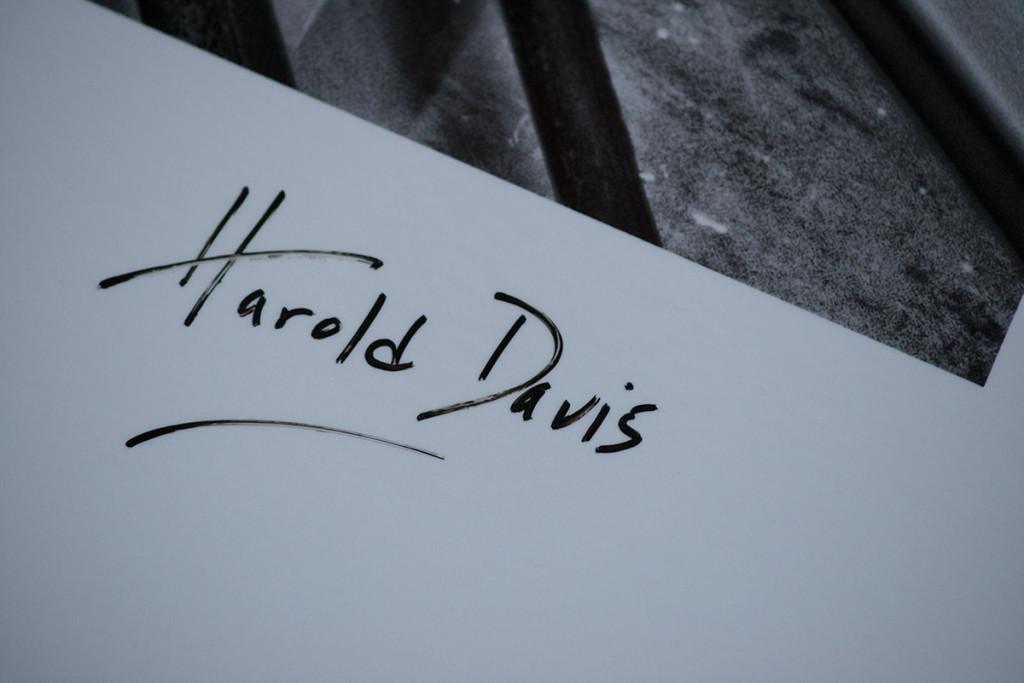

Do you hand-sign or digitally sign your prints?

To digitally sign a print means to add a signature within the computer file used to make the print. Hand-signing means that each print is individually signed using either a pencil or pen. All of my prints that are intended for art galleries or collectors are hand signed.

I use an archival pigment stylus for prints on paper where the signature will work best with ink, and a nice sharp art pencil (usually HB grade) for substrates where ink wouldn’t be best, such as Japanese washi.

It’s very easy to tell the difference between digital signatures and hand signatures; usually one can spot the difference at a glance.

Is a certificate of authenticity available?

Yes, a Certificate of Authenticity is available for prints purchased from my studio on request at the time of purchase.

EdB

16 Jan 2015Thanks for writing this, Harold, it is extremely useful. I’ve spent as much time working on printing over the last couple of years as in on-screen development and have found there is minimal information on the subject of producing good prints. Perhaps topic for a book?

William Bogle Jr

28 Jan 2015Great article Harold. I love to sign my matte paper prints, such as Entrada Bright, in pencil as the paper takes the lead so well. I thought your comments on limited editions was so on point. David Vestal did a survey years ago and found out that most photographers that did not limit editions actually printed fewer prints. I think few photographers would be willing to destroy the file at the end of the limited edition prints.

I love Moab Entrada paper.