[Note: this is a reposting of a story originally published in July 2005.]

© Harold Davis – Thousand Islands Lake, Ansel Adams Wilderness, July 2, 2005

About a week ago I organized a solo hiking trip to the Ansel Adams Wilderness. The Ansel Adams Wilderness is administratively part of Inyo National Forest, and lies just south of Yosemite National Park in the high Sierra. It’s accessible to hikers from the eastern slope of the Sierra Nevada Mountains off Route 395, which runs past Mono Lake and through Owens Valley. Here’s the general area in question shown as a Google Satellite image. My goal was to go camp beside Thousand Islands Lake, where I’d spent some time thirty years or so ago in my backpacking glory years. The lake is nestled under Banner Peak and Mount Ritter. I thought it would make good photographic material for the digital equipment I’ve been playing with lately. It’s spectacular country, and there are many islands in Thousand Islands Lake, although probably not one thousand of them. (You’d hardly know there were any from the picture above with the lake mostly under snow.)

I had about a day to make my preparations. I finished up Chapter 9 of the book about Google I am working on, and swung into gear. It had been a while since I had been backpacking, so I needed to remember what stuff to bring, to shop for food, load a backpack and make sure I could carry it, and get a wilderness permit.

The wilderness permit part of it was easy. I called the reservation number at Inyo National Forest, and for $5.00 on my Visa card got a wilderness permit which would be left for me in the night drop box at the Mono Lake Visitors Center in Lee Vining. Lee Vining is on the eastern side of Tioga Pass. The pass had opened a few days before following one of the heaviest snow years in recorded history in the Sierras.

As I chatted with the reservations ranger, he told me that there was lots of snow (I knew that already), and that I probably wouldn’t see too many people or mosquitos on my trip. I said both of these were good things. He also told me I needed to carry my food in an approved bear-resistant container. These bear canisters are made of molded plastic and use screws that you turn with a coin (or back of a spoon) to make it difficult for a bear to get inside. Personally, I kind of think that if a bear can get into a car trunk, a bear can probably get into one of these things. But regulations are regulations, so I added a bear food storage thing to my list of supplies to buy at REI (Recreational Equipment).

I also wanted to figure out a way to store my digital images in the field without having to use a whole mess of memory cards, so I bought a 40 Gigabyte battery operated photo storage gadget. I’ll be writing more about digital photo field storage options in a subsequent blog entry.

After my day shopping, organizing, and preparing I loaded my food in the bear canister, and the canister, sleeping bag, tent, cameras, and so on, into my backpack, and shouldered the backpack. With my backpack, probably about forty-five pounds, and in my hiking boots, I walked to the top of Marin Ave, a pretty straight up road that goes up about 1200 feet here to the top of the Berkeley hills. I was sweating, but I could do it! I felt good. I though to myself, “I may be fifty-something, but I’m fit – and you’d never know it!”

Wednesday morning early I left the three boys and Phyllis, drove out through the Bay area sprawl, across the central valley via Oakdale and Manteca, and onto the North Yosemite highway at China Camp. From there, after passing the park entrance station at Crane Flat, I turned onto the spectacular road that goes up to Tulomne Meadows and Tioga Pass.

On the other side of the mountains, in Lee Vining I picked up my wilderness permit – once I signed it my permission to hike was official! – had some dinner in a restaurant, and headed for a campground near my trailhead.

The trailhead I was going to use, Rush Creek, starts from Silver Lake at an altitude of about 7,200 feet on the June Lake loop. Grant, Silver, and June Lakes are a kind of messy resort (with a ski lift and many trailer parks) the first stop south of Lee Vining and the Tioga pass road. So I drove south for about ten miles, and then turned right towards the mountains. As I passed Grant Lake, the high rolling sage brush turned to mountain forest, rock and snowy vista.

The next morning I grabbed a massive breakfast at the Silver Lake Resort. For the record, I ate “Miner’s hash – everything but the kitchen sink.” I can’t vouch for the kitchen sink, but it certainly had eggs, ham, bacon, and potatoes. They are big on gold and silver mining and hearty eating in the tourist enclaves of the eastern Sierra.

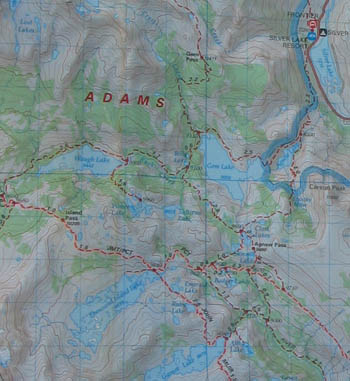

Next, I stuffed my tent back into its sack, parked by the trailhead, and started up. Here’s a map of the area (you can click it for a larger size):

It’s amazing how easy it is to leave our everyday world and enter a completely different universe. This other universe is one where issues are simple: survival, not falling down a cliff or into a hole in the snow, being warm and dry, having enough to eat, and (if you are fifty-ish with kids) not having a stroke or heart attack alone in the wild. The wilderness is grand and majestic and magnificent – but it is utterly alien to us, and does not care in the least about us and our concerns, our well-being, or whether we live or die. Depending upon how you look at things, this is either comforting or terrifying (or both). Hikers do vanish each year in the Sierran wilderness; for example, probably no one will ever know what happened to Fred Claasen or Michael Ficery other than that they died.

Perhaps it is a good time to start making clear the mistakes I made on my journey through one of these cracks into the alternate universe that is the wilderness. First, I wasn’t really paying attention when people (such as the reservation ranger) told me about all the snow, and how empty the Sierra wilderness was this year. I also wasn’t taking the time to get adjusted to the change in altitude. I drove from sea level to above 7,000 feet in one day, and then started hiking up. No wonder I didn’t feel so good. My head was pounding, and my breathing labored. Stay tuned for one big whopper of a mistake to come (though obviously I am here to write about it).

The Rush Creek Trail goes up on a long diagonal above Silver Lake. You can look down at the normal world of people fishing on the lake:

Around the bend, Rush Creek pours out of Agnew Lake – this year, a great deal of water (which might have made me stop to think):

The trail on its way up to Agnew Lake somewhat bizarrely crosses a cog railway twice. This railway is used by Southern California Edison, who uses the area for power generation in a modest way. Also on this first bench up, I crossed a snow field (not very hard, but a slip could have been bad news – in fact I later heard someone had been badly injured crossing this patch), and a creek crossing where the bridge had been washed out, both within two miles of the start of my hike. Obviously, I wasn’t paying very good attention. My attitude was simply “Gosh darn I can do this!” Here’s the railway:

Right about at the second crossing of the tracks I met a hiker, my first on this trip. He was an old codger dodger – well, no older than me, but you know what I mean – carrying a day pack and his name was Billy. Billy’s hobbies were leading boy scouts from his home near Ventura into this area and helping with search and rescue operations. He knew this part of the mountains pretty well.

I told him what I was planning: to head up the cliff on the little-used trail on the south side of Agnew Lake, continue past Spooky Meadow, Clark Lake, and Summit Lake, and find the Pacific Crest and John Muir trails near Thousand Island Lakes, camp there a few days, and then head out the same way.

Billy suggested gently that I might want to reconsider. He said that in thie year of extraordinary snow the trail I was planning to take would almost certainly be under snow and probably impassable and dangerous. I should at least scout it, he said, from the other side of the lake before heading up it. Billy also suggested several longer (but less steep and dangerous) ways to get into the high country.

I can say with absolute certainty that I paid no attention to anything Billy the search and rescue codger-dodger said to me. When I got to the junction with the side trail I’d been planning to take – my trail led off to the left on the far side of the lake – I took it without looking ahead. I did notice that there was no sign marking my trail. I later learned that they didn’t post “my” trail because they wanted to discourage people from using it.

For the first part of the trip up the steep side of the lake, things seemed OK, and well steep. Here’s a picture with the trail outlined in red so you can see it:

I took the photo from the other side of the lake on my way out a few days later because I wanted to get a good look at where I had started my walk on the wild side. The first part up along the side of a steep scree field was no particular problem, although I did have to pause to take a breath frequently. When I got to the trees shown in the photo I had to start pulling myself up hand over hand, backpack and all. As I continued up the snow crossings started to get more and more difficult and scary. Some were undercut with fast running water, and I knew a collapse was possible at almost any time in these conditions of brutally hot sun and massive snow. As I’ve said, I drew the trail into the photo above. The part I drew in towards the top was the last I saw of the trail for many miles – it vanished under a snow field, and didn’t reappear. I began to wonder why I hadn’t brought proper gear for traversing snow – an ice ax, or at least crampons. Gators would have been nice, too, although more a matter of comfort than safety.

At some point when I was fairly shortly above the area shown in the photo I realized that I had lost the trail in a terrain of infinite snow and steep cliffs, and that it was probably too dangerous to go back down the way I had come.

This story is continued in Does the Wilderness Care about Me?

It concludes in There and Back Again