The Steamboat Slough Bridge, shown here from underneath, was built in 1924. According to HistoricBridges.org, this bridge is a good example of a Strauss heel-trunnion bascule bridge. Despite some repair work in 1953 and again in 2000, the bridge is much like it always was.

Something of the same sort can be said for the Sacramento River delta. This is an area that time forgot, almost a foreign country in the backyard of the San Francisco metropolitan area, and adjacent to Sacramento, the California state capital.

Driving the hour or so from my home in Berkeley to California Route 160, also known as River Road, which bisects the delta, my friend Jim and I weren’t sure what to expect. We found a vast low country, only a few feet above sea level, formerly wetlands and marsh, now ranch and agricultural land. Wind turbines and transmission towers sit astride the low-lying landscape.

The innumerable channels of the Sacramento River have created a maze of islands, with a reedy fringe on the banks and agriculture inland. Small roads cross the channel on bridges like the one across Steamboat Slough, or one of the many operational car ferries.

There are a few towns in the Sacramento delta, principally Ryde, Walnut Grove, and Locke, along with trailer parks and vineyards.

Ryde’s principle tourist attraction is Foster’s Bighorn—a bar and lunch place featuring hundreds of stuffed big game heads. They were really gracious about letting me photograph inside with my camera and tripod, but I really can’t bring myself to process any of the images. I also don’t see how one could really enjoy one’s brisket sandwich with the myriad glass eyes of lions, bears, and elephants staring at one.

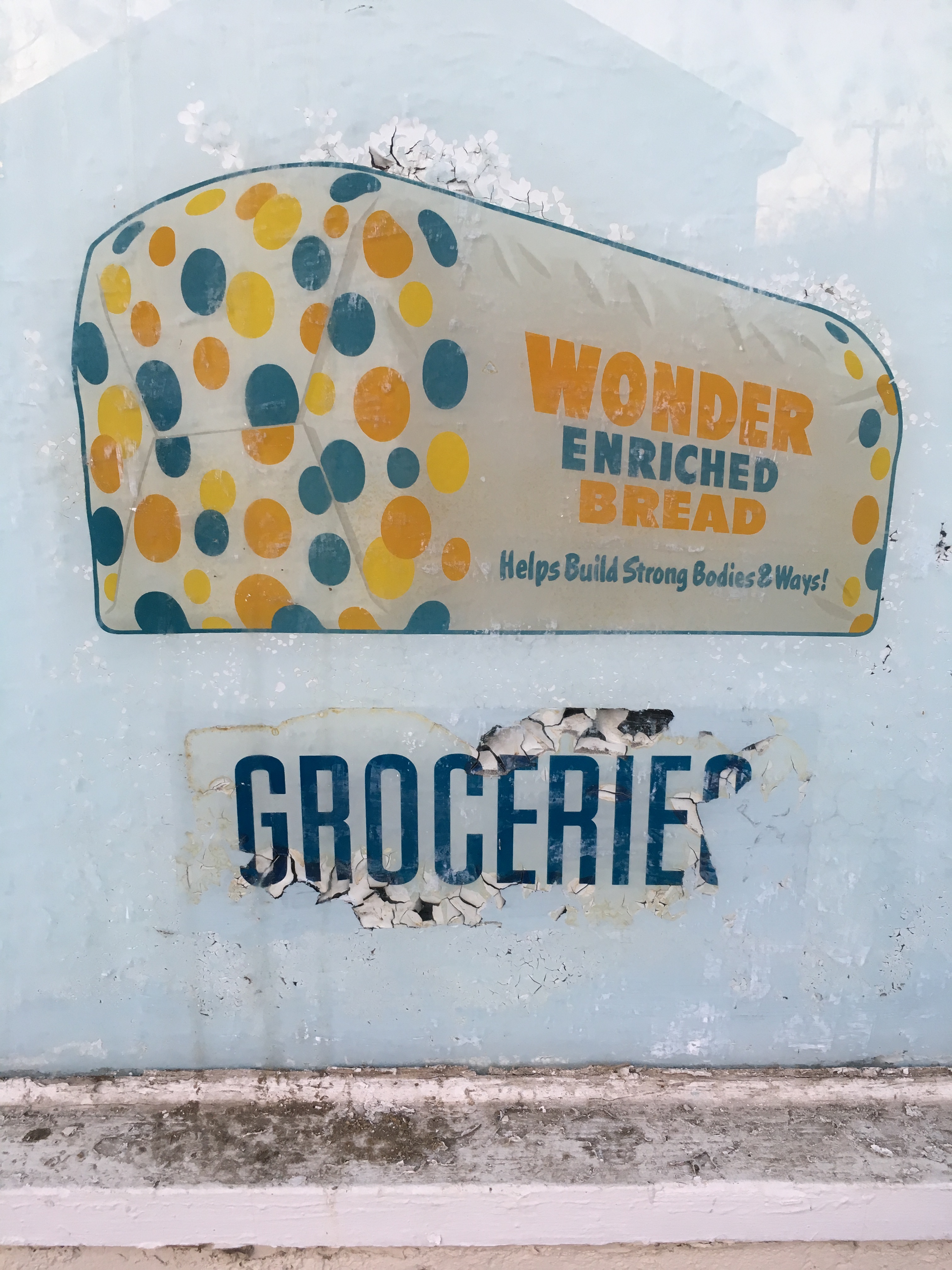

Locke was a Chinese community, which swelled with seasonal agriculture hands who worked the delta. Today it seems to be an outing destination from Sacramento, with Chinese restaurants, a Chinese herbal medicine practitioner, and even the “Locke Ness: Things Old & Odd” curio museum and shop. Nearby Walnut Grove is the largest town in the area, and features grocery stores with ads from the 1950s (when was the last time you saw a loaf of Wonder Bread?).

There’s a sense of strangeness and otherness about the delta, and also, in a weird way, of permanence. This is country that makes you think that AI, fake news, and all the other stuff we think about every day, can only be the invention of some dissonant, alternative sci-fi future.

Threatening this permanence is the Delta Tunnel Plan. This hypothetical project, beloved by Governor Brown, and mired in innumerable law suits, would build two four-story tunnels under the delta to carry water from the delta to the Central Valley, and the always-thirsty cities of California’s arid south.

Businesses of all sorts around the delta have anti-Tunnel Plan placards prominently displayed. Should the Tunnel Plan ever come to pass, it will drain the delta of the one resource it has in abundance—good, clean, flowing water—and change the land more than any other human action since the marshes were drained in the years following the great California gold rush. As with any project that projects changes of this magnitude, the downstream consequences—to the great Bay of San Francisco and beyond—are hard to know.

Jim Ruppel

15 Dec 2018These are things that need to be said. Keep up the good work.