© Harold Davis – Looking towards the Minarets from Summit Ridge, July 1, 2005

In the first part of this story, I told how an excess of enthusiasm for wilderness backpacking and a desire to try out some new digital photography equipment led me up the side of a valley hung with steep snow fields undercut with rapid waterfalls. The trail had vanished under the snow. I didn’t have an ice ax or crampons for traveling on snow and ice, and it seemed way too dangerous to go back down the way I had come.

Getting myself into this situation was possibly foolish of me. Actually, it was obviously extremely downright stupid on my part. It also showed a certain amount of inattentiveness – to the snowpack situation in the Sierras this year, and to the warning that Search-and-Rescue Billy had given me. My fixation on getting away from the kids for a few days, on being a wilderness photographer again, and reliving my life style from my twenties even though I am in my fifties had got me into a fix. Maybe that’s why “fix” is the root word in “fixation”.

Anyhow, as the day passed and I continued up and across the snow in the general direction I thought the trail would have meant to go if there hadn’t been any snow, I began to realize that I was very alone, that I was in a fix that might even be life threatening, and that I would have to figure out how to get out of it on my own.

After I got up the cliff-covered-with-snow-which-there-was-no-going-back-down, I passed Spooky Meadow. Here’s a picture:

It looked pretty spooky to me, I guess, but not like much of a meadow. A little further on, there was more snow. Hard to know which way to go, though terra firma did stick out of the snow from time to time, like in this picture of one of the Clark Lakes:

The next memorable landmark was when I slogged my way to the junction with another, somewhat less steep trail that headed back down to Gem Lake. I knew that I was at a junction with this trail because the junction sign post stuck out of the snow. Otherwise I wouldn’t have had a clue. I thought about heading down this trail. Search-and-Rescue Billy had suggested it as a less steep topography than the way I had come up. But the thought of turning around with my tail between, well between my backpack, was too much for me – I also didn’t like the idea of trying to follow a trail (a trail that didn’t really exist because it was under snow and that I didn’t know) down a steep mountain.

Had I been thinking ahead, I would also have wondered about crossing Rush Creek at the bottom of the valley near Billy Lake. (As Search-and-Rescue Billy had remarked, “nice of them to name a lake after me.”) But I wasn’t pondering the issues raised by high water crossings yet, just stuck in the mire of crossing endless snow.

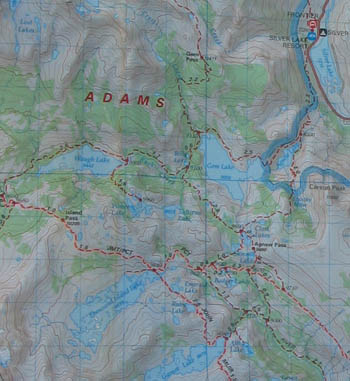

Here’s a map of the area (you can click it for a larger size). The trail junction I’m talking about is 0.7 miles below Agnew Pass on the map:

By now I was getting pretty tired, and the day was getting on, but there was no place to camp. I also still had vague fantasies of making it to Thousand Islands Lake before dark, which had been my (very misguided) plan.

I continued on past a variety of snow fields, small lakes, and slopes ranging from mildly steep to pitched catastrophically into the small lakes until I was able to orient myself by an obviously heart shaped lake. You can see this lake on the map if you look hard right above the word “Summit” on the larger version of the map.

It’s clear that the trail passes over a ridge at the bottom of the heart, but it was equally clear to me that I wasn’t going to pass over this steep, slippery ridge without glissading down the snow into the little heart-shaped lake. Said lake, by the way, was half frozen and had no obvious way of egress because of steep banks if I had plunged into it, leaving me with more to worry about than the effect of ice water on my digital equipment.

Well, getting myself into this predicament may have been a foolish mid-life crisis blip kind of thing. But once there, I do have to say without boasting that my wilderness navigation skills are superb. I don’t know whether it is my eastern European Jewish ancestary, or my Native American progenitors, but I can find my way anywhere. Blind fold me, spin me round and round, I still know my directions and how to get to anyplace at all. I also know how to read a map. It’s probably not genetics at all, just one of those things that some people do and others don’t. But it’s a good skill to have if you are ever caught in a snow-clad wilderness empty of people.

So as an intrepid path finder, acclimated to sea level and not 10,000 feet elevation, carrying a fifty pound pack for the first time in years, not to mention too much bulge around my middle, I actually made a good decision. I said, no matter what I am not attempting to traverse slopes that I think may be too dangerous. That ruled out following what I deduced as thedirection of the trail. Instead I set out in the opposite direction, up a safe but do-able snow field without tremendous exposure.

The snow field led to a summit ledge that I could follow. By now I was downright exhausted. I looked around. It seemed like a pretty good place to camp, with a great view across the valley towards Banner Peak, a view of the backside of the minarets, and further off towards the south the high creast of the Sierra headed towards Mount Whitney orange in the late afternoon sun. There was also a waterfall tinkling into the valley out of one of the snow fields. Here’s what the place looked like:

I put my pack down and explored. Not fifty feet from where I had stopped, I saw the trail once again emerging from the snow. It was my first site of the trail in quite a few miles, and I found it heartening. The view down the valley in the direction I wanted to go towards Thousand Islands Lake also looked blessedly free of snow:

My spirits went up. It looked like maybe I wasn’t so crazy after all. I had a nice campsite (my yellow tent, bought on sale from Sierra Trading Post years ago and never used, went up snug and cheerful). A musical waterfall played its wonderful melody as it ran out of a snow bank and I cooked dinner. The trail ahead looked to be obvious and relatively clear of snow. As the sun set I put the Nikon D70 on my tripod and took pictures including the one at the beginning of this installment of the story and this picture:

For another picture from this camping spot, taken at dawn, see this entry.

So I should have been relatively content. It at least seemed like I’d made it through the worst and had good conditions for the walk over to Thousand Islands Lake in the morning. I had a snug, harmonious, and spectacular place to camp. But all was not right for me.

As I lay in my sleeping bag exhausted beyond belief I realized I didn’t care about the beautiful wilderness around me. After all, it didn’t care about me. Banner Peak was completely indifferent to me. Banner Peak didn’t care if I lived, or I died, or if I ever saw my family again, or if I had a pounding headache from the altitude.

And all I wanted was to be out of there. I wanted to be back at my car at the trail head. Most of all, I want to be safe and snug with my family.

This story began in A Walk on the Wild Side

It concludes in There and Back Again

Pingback: Photoblog 2.0: » Photoblog 2.0 Archive: » A Walk on the Wild Side

Pingback: Photoblog 2.0: » Photoblog 2.0 Archive: » There and Back Again

Pingback: Photoblog 2.0: » Photoblog 2.0 Archive: » A Lost Hiker

Pingback: Photoblog 2.0: » Photoblog 2.0 Archive: » A Walk on the Wild Side

Pingback: Pagan Goddess