Were these images really made with x-rays? The same kind of x-rays used in a medical office? Yes, they were.

It is accurate to call these x-ray captures “photos” and to call the process “photography”? I think so. The process involves exposing a sensor to electromagnetic radiation. This is exactly what happens with a conventional camera: electromagnetic radiation emitted or reflected by the subject of the photo is captured for the duration of the exposure.

Most, but not all, of this radiation captured conventionally is on the visual spectrum, meaning it can be seen by human eyes.

But a DSLR sensor will also record radiation that is beyond the visual spectrum (the camera “sees” more than we do, particularly when it is dark), and conventional cameras can be modified to capture the infrared spectrum (IR) (at the other, longer, side of the visible spectrum from x-rays, which are shorter than visible light in terms of wave length).

IR captures are usually called “photographs” without any particular distinction from conventional, shorter wave-length visible light captures. Comparably, I believe that x-ray exposures, which capture an even shorter frequency radiation wave than conventional, visible-light exposures, should use the same terminology.

Certainly, as a photographer, the process of making an x-ray exposure feels very familiar!

What gear did you use to make these images? We used an x-ray system designed for mammography for these images. I am hoping to use some other kinds of x-ray equipment in the future.

Is it safe? I hope so! We used a leaded-glass shield while the exposures were made (just like the normal operator of the x-ray machine), and I am told that as a statistical matter, any additional exposure to radiation I may have encountered is not likely to increase my lifetime risk of getting cancer.

How did you get access to the equipment? My friend and collaborator Dr. Julian Köpke is a physicist and medical doctor in a radiology practice. We used the gear in his radiology practice after office hours.

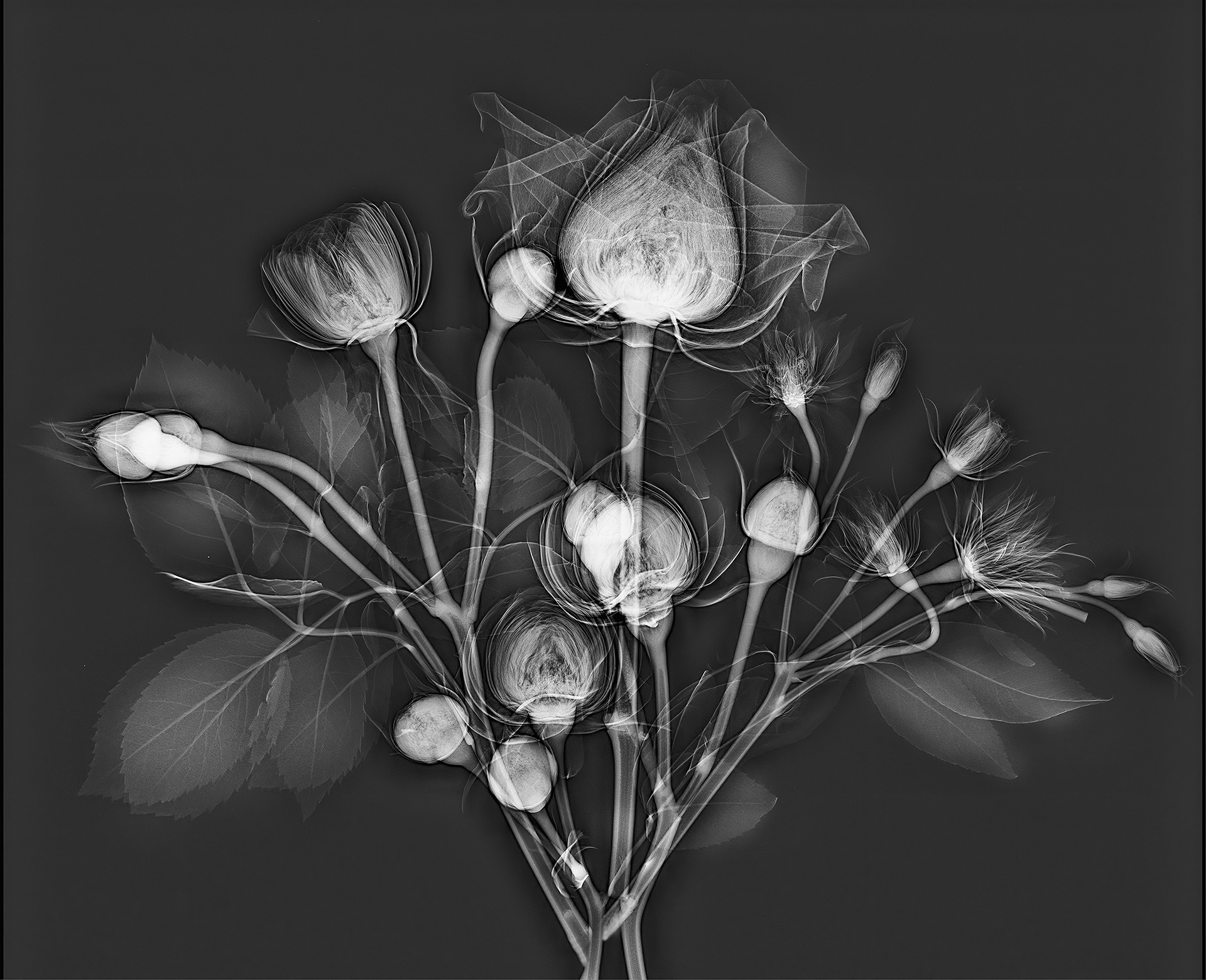

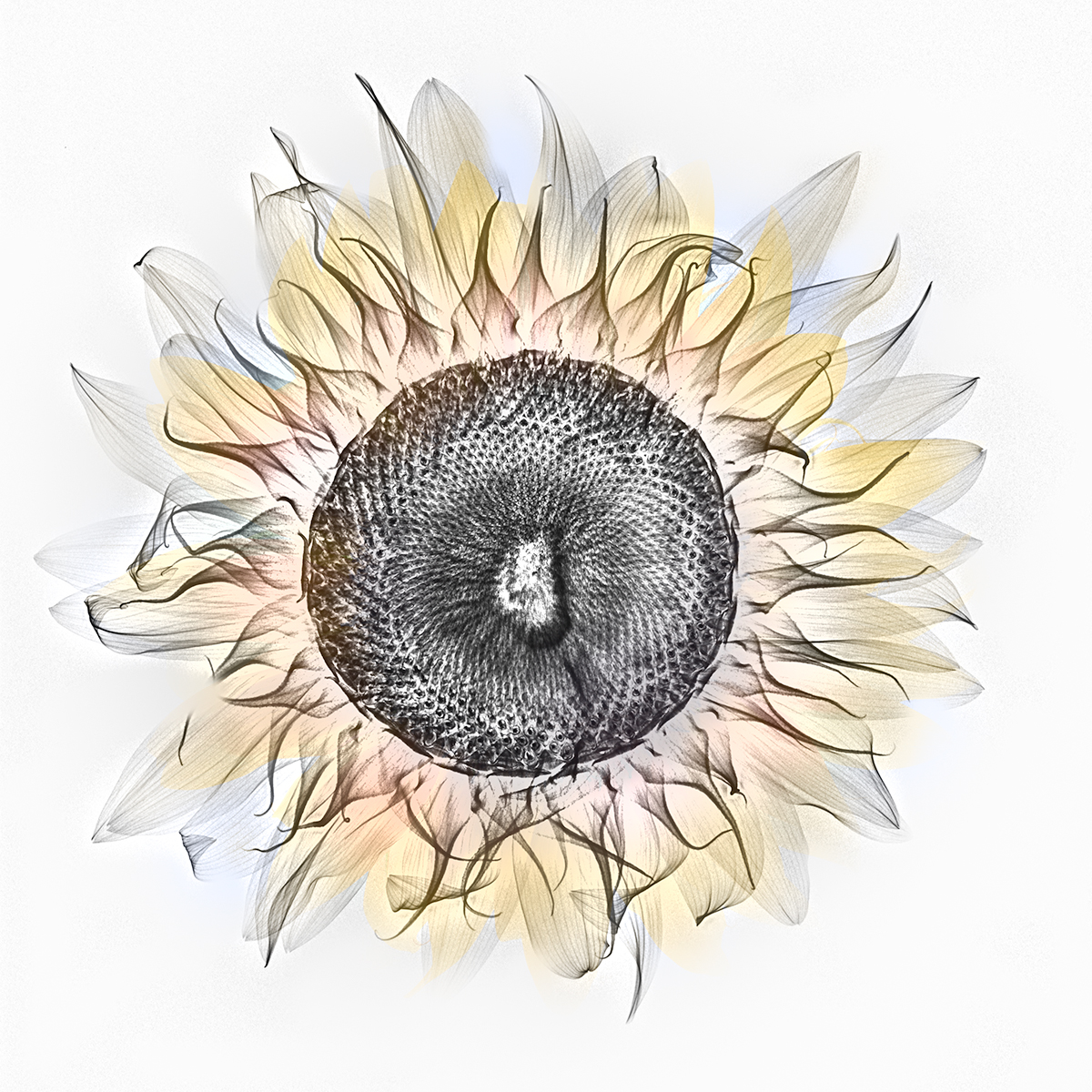

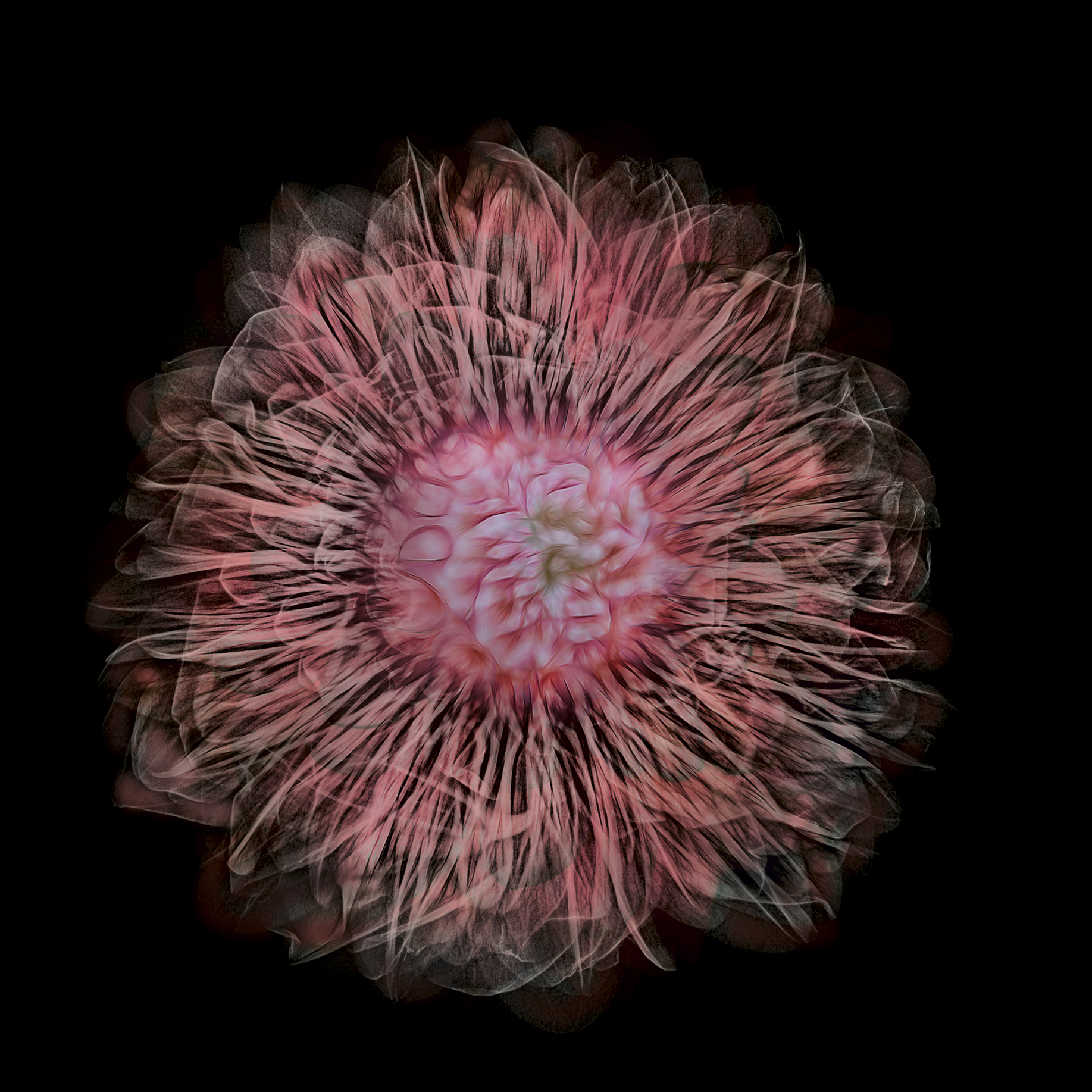

What is the creation process like? The process of making these x-ray images of flowers and shells is more like making a photogram—what Man Ray called a rayograph—than it is like using a conventional camera. The flowers are arranged on top of the capture medium, in this case a digital sensor and then exposed. But the exposure is to x-rays rather then to light in the visible spectrum, as in a photogram, where objects are placed on top of a photosensitive medium (historically, more oftern emulsion-coated paper rather than a digital sensor).

The x-rays reveal the inner form and shapes rather than the surface manifestation of the object. It is possible to look at the petals of a flower as though they are gauze or veils, and to see the capillaries within a leaf.

Rather than the surface of a shell, when the x-ray “camera” is pointed at a shell, the inner spirals, shapes, and forms of the structure is revealed.

The medical x-ray process involves both generating the x-radiation, and capturing it on a digital sensor. In this sense, it is analogous to firing a studio strobe and capturing the light waves emitted on a standard camera sensor. With the stationary medical x-ray device, I was reminded most of an old-fashioned analog darkroom enlarger, where the light beam from the enlarger is captured on media directly below it (photographic paper that is sensitive to light in the analog darkroom process).

What turns out is that x-radiation has very different properties as the electromagnetic source than the visible spectrum. X-rays both scatter and decay, in a way that the visible light we are used to does not. So to get good x-ray compositions, it was necessary to work with the characteristics of how the x-radiation emitted from the mammogram system we used would be captured by the digital sensor, and to arrange the flower compositions accordingly.

To put this comprehensibly, the mammogram system was designed to best capture the shape of the human female breast. We got better results to the extent that our composition could mimic this three-dimensional shape and positioning.

In a typical setup, we’d arrange the flowers on a sheet of plexiglass, and align the plexiglass with marks we had set up on the machine. This was to enable light box photography to create the “fusion” versions of these images. Then Julian and I would huddle behind the operator’s leaded glass shield as Julian operated the machine.

What is an x-ray? The visible light that we see consists of waves (also particles), with wavelengths emitted or reflected along the electromagnetic spectrum. Visible light ranges from 400nm to 750nm in terms of wavelength. In comparison, the x-rays we used had a wave length of roughly 0.04nm (or shorter in wavelength by a factor of about 10,000 than visible light).

What do you use for post-production? Photoshop.

You’ve called this work a “collaboration.” Please explain. As I’ve noted, my friend and occasional student Julian is a physicist, medical doctor, and radiologist—with an interest in photography and astro-photography. We’ve collaborated and worked together to create these images, forming an ideal partnership of the technical and scientific with the artistic side of things!

Have you used x-ray photography to capture anything besides flowers? So far, besides flowers, I’ve made a few x-ray images of shells. I do hope to experiment with other subject matter when I can.

Do you have ongoing plans to do more with x-ray photography? I’d like to very much. I’m very pleased with the way this collaboration has gone so far, but obviously there is much more that can be done from an artistic perspective.

Where can I see more of your x-ray images? Check out my online gallery of X-Ray and Fusion X-Ray Photography and the X-Ray category on my blog.